Image of God

SJF • Trinity Sunday A 2014 • Tobias S Haller BSG

God said, “Let us make humankind in our image, according to our likeness...”

And so it begins... We heard this morning the unfolding of the beginning of all things, the creation of the world and all that is in it, as recorded in the first chapter and the first verse of the second chapter of the first book of the Bible, Genesis. In this powerful vision of creation, God is portrayed as a master architect — as in William Blake’s famous illustration: God sets his compass on the face of the deep. Blake — a master craftsman himself — portrays God as the supreme Master Craftsman, the heavenly architect at work.

So too, the language of this creation story echoes the building of the earthly temple. This is fitting. For just as the temple was God’s symbolic dwelling, all of creation is a habitation for the Most High. Of course, as Solomon would later say when he built the temple in Jerusalem, even heaven and the highest heaven can not contain the greatness of God, how much less this earthly temple. Yet we know that God does visit these earthly habitations — in ways that will become clear, I hope, in a moment.

In the cosmic temple described in Genesis, the dome is the roof of the sky, and its foundation is the earth. The waters are gathered together into one place, into just such a basin as was featured in the temple in Jerusalem, a huge bronze basin in which the priests would wash before they entered the inner courts. The vegetation reflects the decoration of the temple, the walls and columns, carved with fruit, vines and branches. The great lights of the sun and moon are like the huge bronze lamp-stands that stood in the temple court. Then, to provide the multitude of sacrifices, all the living creatures are created. Thus the temple is almost complete, ready for the worship of God.

I say, almost complete. What is missing? Well, in most temples of the ancient near east, in the innermost portion, in the shrine of the holy of holies, you would find an image of the God that the people worshiped, to whom the temple was dedicated. And this is where we come in. As you know, God forbade the Israelites making and worshiping graven images; and in the temple in Jerusalem, in the Holy of Holies, there was no image of God — but instead, the ark of the covenant and the cherubim who served as the throne of the invisible God.

But in the cosmic temple described in Genesis, God does create an image, a likeness, to represent God, and to take its place at the center of creation, in the holy of holies. God creates humanity.

This tells us that the author of Genesis understood humanity as the crowning achievement of creation, but even more, to be an image or likeness of God. It is as much as to say, If you want to know what God is like, look at human beings.

Now, this doesn’t mean that God has a head or two arms and two legs. And we also have to acknowledge, especially given the rest of Genesis, to say nothing of Exodus, Numbers, Deuteronomy and all the rest, that we are to look to the best of humanity — humanity as it is meant to be at its best — if we want to gain an idea of God’s nature. So what are people like at their best: and how do we reflect the image of God?

+ + +

We find an answer to this question in the closing words from Paul’s Second Letter to the Corinthians. “The grace of the Lord Jesus Christ, the love of God, and the communion of the Holy Spirit be with all of you.” Grace, love and communion: these three qualities of God, reflected in humanity, are facets of God’s image and likeness; and these facets, like the persons of the Holy Trinity itself, are related and connected, much as the human and divine natures are interconnected in the person of Jesus Christ. What’s more, the mystery of what it means to be human, and the glory of what it means to be divine, find their perfection in Jesus Christ; he is the true image and likeness untarnished by sin: revealing humanity as all that humanity is meant to be, when God created us in the first place. It is in the Incarnation of Christ that we will find the place where the human and divine meet, as the hymn says, “God in man made manifest.”

+ + +

First comes the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ. What is grace? We tend to think of grace as being about style, decorum, elegance. We say someone is “graceful” when they move well. But the grace of God, especially of God in Christ, is about the gift of God and the giving of God, the stooping down and emptying out of the Son of God, the graceful descent from the throne at the Father’s right hand, the choice to come to us, to be with us as one of us, the graceful condescension of Emmanuel — God with us — when the power of God leapt down into the womb of the Blessed Virgin Mary, and the infinite reality of the creator of all that was became, as one old poet so beautifully put it, “compassed in little space.” This is the grace of Jesus Christ, like the grace of the most perfect high-board diver who leaps from the highest point and spins and plummets but then enters the water with only a tiny splash! This is the grace that is a gift: a gift to you and a gift to me, that the Son of God, should for our sake, take our nature upon himself, as naturally as a man or woman puts on a garment perfectly tailored for them — because it was for this reason that God made us in his image in the first place: that one day God might put on our nature with such a perfect fit. This is the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ.

+ + +

Next comes the love of God the Father. And John the Evangelist is the great exponent of God’s love; it is a theme he takes up again and again. It is he who assures us that God loved the world so much that he gave his only Son, so that everyone who believes in him might not perish, but have everlasting life. He continues, that God did not send his son into the world to condemn the world, but that the world might be saved. As John said, In this is love, not that we loved God but that he loved us and sent his Son to be the atoning sacrifice for our sins. So once again, John helps us to see that God’s very being is tied up with the Incarnation, the sending down of the Son of God to be with us, in order to save us. As Jesus said in John’s Gospel, There is no greater love than to lay down one’s life for one’s friends. And this is what God did for us, in Christ, giving himself to save us, even from ourselves.

And as John continues in his First Epistle: “Since God loved us so much, we also ought to love one another. No one has ever seen God; if we love one another, God lives in us, and his love is perfected in us.” You can’t see God — God is invisible — but when we love each other, giving of ourselves for each other, we become so much like him, that the original image and likeness he bestowed upon us in creation begins to glimmer through the stains of sin that we accumulate in our earthly life. Every act of love, every “sending” of ourselves, every stepping aside to honor and serve another, is a reflection of God’s very being. Such is the love of God the Father, who sent his Son to save us.

+ + +

Which brings us to the “communion” or “fellowship” of the Holy Spirit. Of all human love, the love that Christians show to one another, which finds its perfection in the communion of the church, is a revelation of God to the world. John again gives us Jesus’ word on this: “By this everyone will know that you are my disciples, if you have love for one another.” The harmony of the church reflects the harmony of heaven; the unity of the church reflects the unity of God, and the loving fellowship and communion of the church reflects the being of God, who is Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

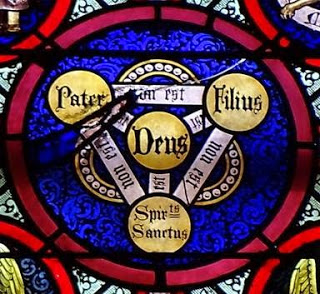

Communion, whether the communion shared by the persons of the Holy Trinity, or the communion shared by individual Christians or by Christian churches, does not mean that everyone is exactly the same. Right in the middle of our west rose window you can see the old emblem of the Trinity: and it affirms the truth that while we believe the Father is God, the Son is God, and the Holy Spirit is God — yet we do not, as the Athanasian creed put it, believe in three Gods, but one God. At the same time, the Father is not the Son, nor is the Son the Holy Spirit. The Three in One and One in Three are united without confusion, but I’m afraid that when preachers start to talk about it they begin get a little confused, and so it’s probably something best not to talk too much about. But you can look at it — you can behold it, there, and in each other, as we reflect the Holy Trinity, God with us, in us, and through us.

This is the great mystery at the heart of the Christian faith. But as I say talking about it has gotten many a preacher into trouble. So I’ll stop while I’m ahead, and remind us that Jesus promised that Christians would be known by our love, not by our doctrine! Instead let me point us back to the primary lesson I hope you will carry away with you this morning.

+ + +

That is, that God made us in his image. That God made us to be like him. That God made us to be filled with the generous grace that suffers for the sake of the beloved. That God made us to be filled with the love that gives without reservation or qualification. And that God made us to be in communion with each other, joined in the bonds of affection through the instrument of God’s unity. May we be One in Christ as Christ is One with God the Father and the Holy Spirit. And may the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ, and the love of God, and the fellowship of the Holy Spirit, be with us all now and forever more.